The Money Trail, Part I: Safe Charitable Giving in Pakistan

Sep 10, 2018

Counter-threat finance—the efforts to reduce the flow of money that funds terrorism and organized crime—has been a key component of the international community’s struggle against terrorism since the terror attacks of September 11, 2001. When we think of counter-threat finance, international banking, money laundering, and oil smuggling come to mind, but we don’t often think of international development.

Counter-threat finance—the efforts to reduce the flow of money that funds terrorism and organized crime—has been a key component of the international community’s struggle against terrorism since the terror attacks of September 11, 2001. When we think of counter-threat finance, international banking, money laundering, and oil smuggling come to mind, but we don’t often think of international development.

While early efforts succeeded in limiting terrorist groups’ access to international financial networks, these groups have fallen back on tried-and-true methods to keep the money flowing by exploiting charitable donations, mining and smuggling of natural resources, taxation, currency exchange, extortion, and criminal enterprises. By gaining control of territory and through carefully designed financial systems, the Islamic State enjoyed unprecedented access to financial resources. If we hope to succeed in choking violent extremist groups’ access to funds, it is time to recognize that development interventions can play a key role. In this, and in a second post, I will discuss how development practitioners can make concrete contributions to reducing extremist group financing and help vulnerable communities avoid inadvertently funding terrorism.

Dangerous Generosity

One of the main pillars of Islam is the injunction to give charity to those in need. Muslims answer this call to the tune of hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of dollars a year. Some estimates suggest that between $200 billion and $1 trillion is spent annually in Zakat charitable donations alone. This figure does not include other forms of Islamic charity such as Sadaqah, Fitrana, Kharj, or Khums. A developing country such as Pakistan, for example, gives more than $2 billion annually to charity—more than 1 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. In just one month during Ramadan 2017, British Muslims donated considerably more than $150 million. It is no surprise that extremist groups want in on the action.

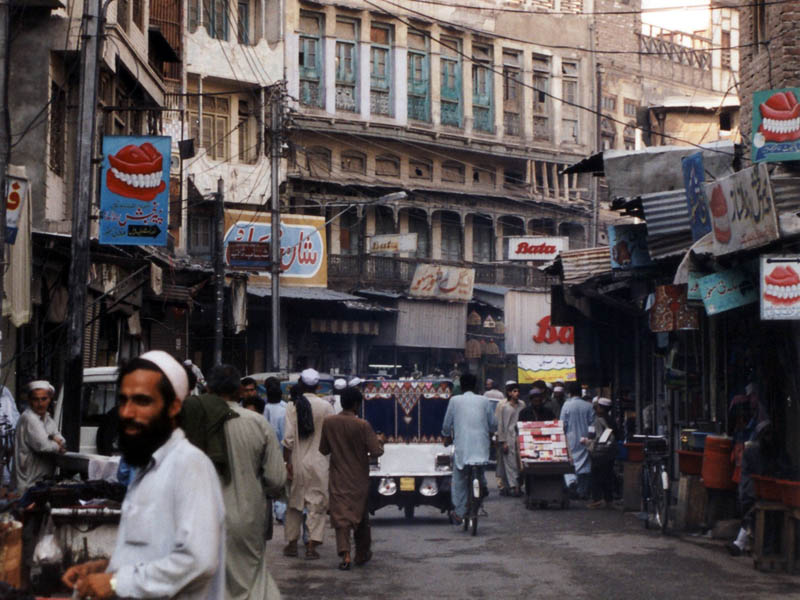

Photo by Jan Chipcase via Wikimedia Commons.

Several aspects of charity in the Islamic world make it particularly vulnerable to exploitation by extremists. First, the Prophet Mohammad directed his followers to give to charity discreetly, saying that the most blessed is the one who “gives in charity and hides it, such that his left hand does not know what his right hand gives…”. This discretion means that charitable giving and organizations are often not exposed to scrutiny, and unregistered charitable organizations are endemic.

Extremist groups take further advantage of the notion in Islam that niyat, or intention, is all that matters in terms of charity. When intention is all that matters, there is little motivation to verify if your donations actually go to people in need, or into the hands of extremists. All of this creates an environment favorable for violent extremist groups that want to raise funds under the cover of Islamic charitable donations. The Government of Pakistan has struggled for years to limit extremist group fundraising by banning and blacklisting suspect charities—though the problem persists.

And this is where development practitioners can make an impact, working with local communities to help increase awareness about safe charitable giving—specifically by working with credible local clerics who can provide guidance on Islamic teaching on charitable giving and show people how to avoid fraud and accidentally contributing to extremists. With the support of local clerics and community leaders, development practitioners can, and do, raise awareness among community members about the dangers of uninformed giving.

In Pakistan, for example, “safe charity” campaigns conducted by prominent local organizations such as the Pakistan Peace Collective (PPC) and the National Counter Terrorism Authority have discovered that most individuals—even those sympathetic to some of the narratives promulgated by violent extremists—express shock and remorse when confronted with the fact that their hard-earned money could be used to kill innocent people. The safe-giving principles under which PPC operates are simple and borne out of knowledge of the communities in which they work. They and their partners work with credible local actors who can speak authoritatively about the Islamic values of charity.

Many of the initiatives conducted by development actors in countries across the Islamic world are deliberately non-proscriptive about which charities Muslims should donate to. The belief is that such proscriptions are counter-productive, particularly when the charities in question are aligned with religious groups. Instead, organizations such as the U.K.-based Humanitarian Forum design activities and education projects to discourage blind giving and to educate beneficiaries about where their donations might go should they not exercise necessary vigilance.

Another key to conducting successful activities lies in providing more nuanced discussions about the nature of giving in Islam, including the importance of giving to those within the community and to less well-off family members—a principle of “charity begins at home,” which is well-established by Islamic jurists. With religion being such a visceral issue, safe charity activities have always had to walk the fine line between being informative yet non-confrontational.

There is some evidence that those who have been informed of safe-giving principles are more vigilant when donating in future and are more likely to spread their new-found knowledge among friends and family—becoming far more credible transmitters of information than strangers from foreign nongovernmental organizations.

A man hands out flyers to Afghan children at a local bazaar in Bagram, Afghanistan.

Safe-giving activities are also being conducted by Pakistan’s Chambers of Commerce, which have recently started to play a tentative role in helping change perceptions among small traders regarding charitable donation boxes. In shops across the Muslim world, one can find collection boxes for various charities. Shop owners rarely enquire about the credentials of the groups placing the boxes. There is anecdotal evidence that campaigns and outreach by concerned umbrella authorities, working in combination with development actors, have helped educate local traders on the dangers of this lack of vigilance and have yielded results. One prominent member of the Islamabad Chamber of Commerce told me he was confident that local traders’ exposure to this type of educational campaign would ensure fewer suspicious donation boxes in shops and a greater vigilance among shopkeepers when allowing boxes to be placed on their premises.

These successes suggest that continuing to educate local communities about safe giving contributes to counter-threat finance and helps end the exploitation of people trying to fulfill their religious obligation to help those in need. Development practitioners need to remain at the forefront of efforts to educate communities vulnerable to violent extremist influence. It is only by ensuring communities are provided the tools and knowledge to remain vigilant against those who would use their generous impulse to sow division and commit acts of violence that this cycle of uninformed generosity can be broken.