Report: Youth and Violent Extremism in Mindanao, Philippines

Sep 12, 2018

Development responses to violent extremism are challenged by a lack of methods for rigorously testing assumptions about and determining the relative importance of different drivers of extremism. DAI’s Center for Secure and Stable States designed and implemented a mixed-methods research methodology for addressing these challenges on the Enhancing Governance, Accountability, and Engagement (ENGAGE) Project, funded in the Philippines by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Our analysis led to surprising empirical findings: less than half of the assumed drivers of extremism are significant predictors of support for violence and extremism, with some functioning in ways opposite to consensus understanding.

Development responses to violent extremism are challenged by a lack of methods for rigorously testing assumptions about and determining the relative importance of different drivers of extremism. DAI’s Center for Secure and Stable States designed and implemented a mixed-methods research methodology for addressing these challenges on the Enhancing Governance, Accountability, and Engagement (ENGAGE) Project, funded in the Philippines by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Our analysis led to surprising empirical findings: less than half of the assumed drivers of extremism are significant predictors of support for violence and extremism, with some functioning in ways opposite to consensus understanding.

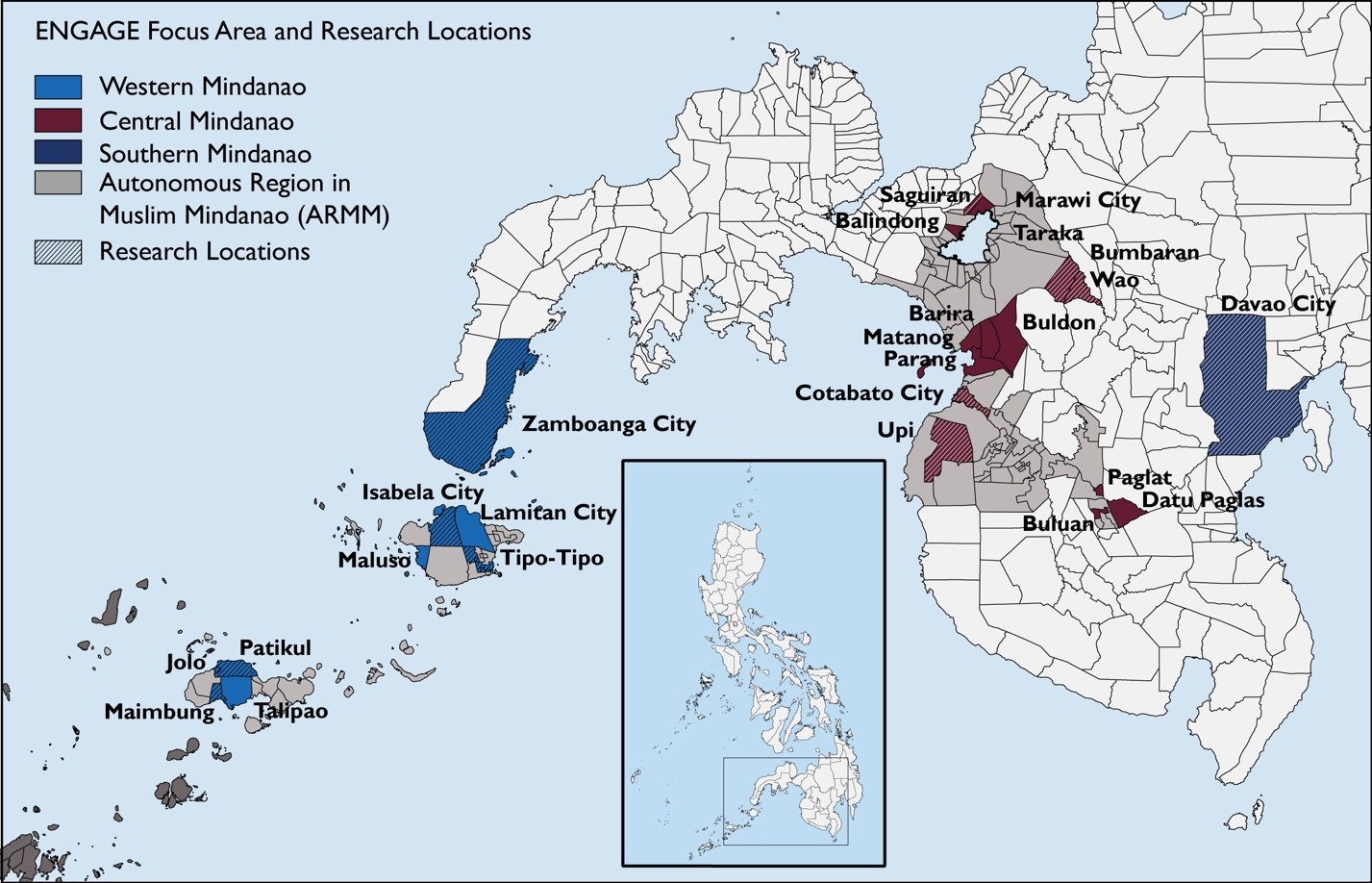

The research started with a list of the 18 assumed drivers of extremism based on a literature review, consultation with experts on extremism in the Philippines, and interviews with academics and local government representatives. To better understand how these drivers form pathways to extremism, detailed case studies of 25 members of armed and extremist groups in Mindanao were collected through semi-structured interviews with extremists themselves, members of their families, and close friends. Next, we designed an innovative quantitative survey questionnaire to test for correlations between the assumed drivers of extremism and support for violence and extreme ideologies. The research team collected a stratified random sample of more than 2,300 young people, including students at five universities and of high school students from 10 randomly selected local government units (LGUs) across ENGAGE’s project area.

ENGAGE Focus Area and Research Locations, Image by DAI

The results show that concerns among young people about corruption, human rights, lack of trust in government, poverty, and unemployment appear not to make them more likely to support violence or extreme ideas. Case studies confirmed that grievances based on poverty, poor prospects for employment, lack of trust in government, human rights, and corruption played a limited role in shaping radicalization and membership in extremist groups. Gender is also not a predictor of support for violence or extreme ideologies, contradicting the assumption that support for violence and extremism is more prevalent among men than women. Support for violence and extreme ideologies correlates with higher levels of community engagement, more acute perceptions of community marginalization and discrimination, lower levels of perceived self-efficacy, more acceptance of revenge seeking and acceptance of a ‘gun culture,’ where power and respect in communities is held by those with guns. One’s family and community networks seem to play a larger role in guiding radicalization and membership in armed groups than any specific grievances or social and economic factors.

These findings carry significant implications for how youth and extremism should be addressed in Mindanao, particularly in the aftermath of the Marawi siege. Additionally, this research approach presents a methodology that can be modified and applied in other contexts to help development practitioners better evaluate assumptions regarding drivers of extremism and design more appropriate programming.