Trauma Awareness and Healing: A Step on the Path to Peace

Apr 10, 2018

I recently traveled to South Sudan to investigate efforts to address trauma in a region that has experienced nearly 27 years of war since the 1980s. As a global development professional and trauma educator, I don’t need to be convinced of the need to address trauma as part of a portfolio of peacebuilding activities. Encouragingly, an increasing number of international donors and organizations are beginning to examine—and program around—the link between trauma and violence.

Over the past two years, for example, the U.S. Agency for International Development in South Sudan has funded Morning Star, a local trauma awareness and resilience program based on Eastern Mennonite University’s STAR curriculum and training. Morning Star, like its parent program Strategies for Trauma Awareness & Resilience (STAR), is based on a framework first developed by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and later tested and adapted by peacebuilding practitioners, among them Olga Botcharova and Barry Hart.

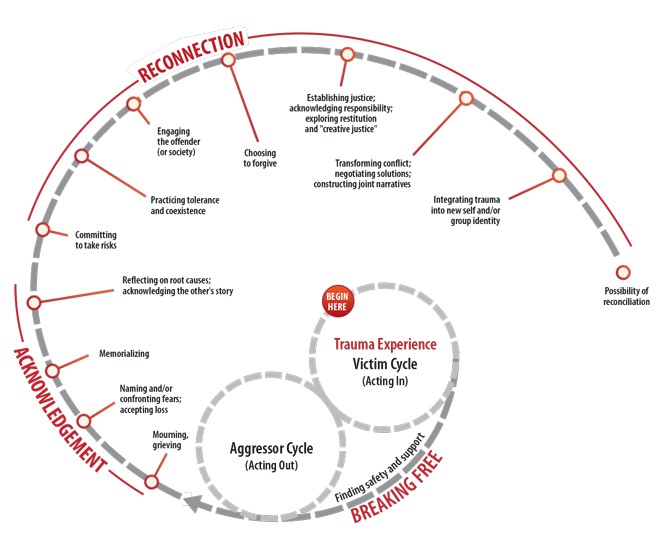

The STAR model, “Breaking Cycles of Violence, Building Resilience,” pictured below, links unhealed trauma with conflict and cycles of violence, drawing on a body of evidence from disciplines including neurobiology, psychology, restorative justice, and conflict transformation.

Source: Eastern Mennonite University

Experiencing traumatic events can cause people to get stuck in cycles of violence, depicted in the model as two closed-loop circles: “acting in” (manifesting in behaviors such as substance abuse, suicidal tendencies, rage, and fantasies of revenge and humiliation) and “acting out” (manifested as domestic abuse, for example, susceptibility to good vs. evil narratives, criminal activity, and violence in the name of honor, justice, or self-defense).

These cycles of violence beget violence, and, in turn, more trauma. Only once individuals and groups break from these cycles can they sustainably support peace at the micro or macro level. In the STAR model, addressing unhealed trauma and its accompanying symptoms, attitudes, narratives, or behaviors is a prerequisite to embarking on the road to sustainable peace, whether that process entails truth telling, creating helpful historical narratives, memorializing those harmed, or administering justice, reconciliation, or social healing.

In South Sudan, Morning Star delivers three- to five-day trainings based on this framework, offering young people, community leaders, clergy, civil society organizations, and health workers:

- An understanding of how trauma affects the brain and body;

- Capacity to identify cycles of violence in themselves, their families, and communities;

- Practical tools to address unhealed trauma in their sphere of influence; and

- A path to begin the journey to healing, reconciliation, and peace.

The Morning Star team believes that people equipped with such knowledge and tools will be better able to draw on inner, familial, and cultural resources to begin to heal themselves and others, and prevent or end cycles of violence (this kind of intervention would not apply to acute or clinically diagnosed cases of trauma).

Other development actors in South Sudan are realizing the potential of trauma healing. The Foundation for Democracy and Accountable Governance (FODAG), a South Sudanese organization, recently started providing trauma awareness training in addition to its suite of democracy building activities. FODAG Executive Director Jame David Kolok explained to me that the foundation had begun collecting testimonies to support the case for future judicial processes but realized that in order to ask people to share their stories, the foundation would need to address trauma. FODAG’s realization is backed by science: Unhealed trauma can create real mental barriers that inhibit victims of violence from telling their stories. If victims can’t recount their stories, then truth telling, transitional justice, and reconciliation are out of reach.

My research in Juba suggests a high demand for such trauma awareness training. After my meetings in South Sudan, for instance, several people emailed me asking how they could access trauma training for themselves or their communities. Similarly, the Morning Star master trainers can’t keep up with demand; as soon as they finish a training, they begin fielding calls from participants requesting training on behalf of others or asking for additional resources.

How can we develop a coherent, evidence-based, and thoroughly evaluated strategy for fully integrating trauma healing into development programming in post-conflict contexts? Building on the foundation established by pioneers such as Morning Star, I offer three areas on which to focus:

- Develop a robust monitoring and evaluation strategy: At present, the Morning Star program measures pre- and post-training knowledge of trauma and collects anecdotal evidence of impact. Ultimately, however, we need to demonstrate that trauma awareness and healing services have a positive impact on attitudes and behaviors, empowering beneficiaries to choose peaceful responses to violent provocations or local conflict, as well as actively support peace during national and local peace processes.

- Define “do no harm” principles in trauma programming: Addressing trauma, even if it’s just education, is psychosocial work—we’re addressing a phenomenon rooted in the deeper layers of the mind and body. How deeply can we go in communities where there is no mental health infrastructure? Can we responsibly train community health workers in this sensitive work? For people who have learned to dissociate to survive, do we do more harm than good by resurfacing trauma in a context where clinical psychiatric resources are minimal? These are questions we should examine closely.

- Think strategically and unconventionally about who to target for trauma activities: Given short program life cycles and limited funding, we must be strategic about who we reach with training and services. How do we decide who to train to have the most impact on cycles of violence? We might want to target community-level and national influencers—in a place such as South Sudan that might be clergy, traditional leaders, or government officials—but we’ll also need to reach current and potential perpetrators of violence, such as military or militia leaders, acknowledging that they are also likely victims of violence acting out their trauma. We might also want to target youth, as their resiliency is so critical to the future stability of a nation. The strategy will differ for each program and context, but if we want to break cycles of violence we’ll need to think and program beyond our comfort zone.