Words Matter: Pastoralists and Identity in the Sahel

Feb 26, 2018

It is broadly understood that language—especially generalizing and dehumanizing language—can play a central role in fostering communal violence. William Donohue has shown how the language of classification was a key early warning in the Rwandan genocide, for example. Such instances should remind the development community to be mindful of the words they use, however innocuous they may seem. Case in point: a term often used in discussion of economics and conflict in the African Sahel, “pastoralist.”

It is broadly understood that language—especially generalizing and dehumanizing language—can play a central role in fostering communal violence. William Donohue has shown how the language of classification was a key early warning in the Rwandan genocide, for example. Such instances should remind the development community to be mindful of the words they use, however innocuous they may seem. Case in point: a term often used in discussion of economics and conflict in the African Sahel, “pastoralist.”

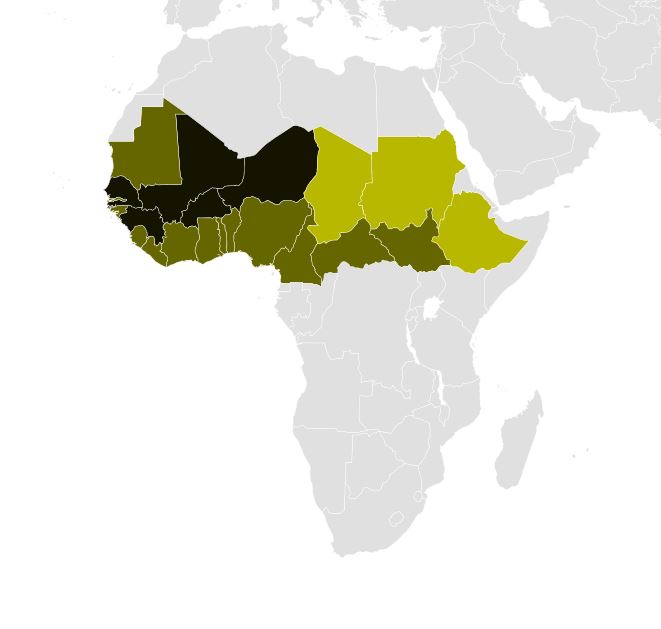

Spanning the African continent, the Sahel is culturally, linguistically, and ethnically diverse, home to various ethnic groups that don’t fit neatly into the national borders of the countries making up the region. One such group is the Fulani, whose 20 to 25 million members live in 20 sovereign states and speak numerous languages, even though they share cultural and behavioral patterns passed down through generations.

Distribution of Fulani people in the Sahel and West Africa, where the darkest color is the heaviest concentration of Fulani. (Map by Sarah Welch via Wikimedia Commons).

One would think that a group as expansive and diverse as the Fulani would defy caricature and stereotype. But the Fulani find themselves referred to more often than not simply as pastoralists by development professionals and international organizations. This generalization is both inaccurate—it is estimated that only one-third of Fulani are herders—and potentially harmful, especially at a time when economic stressors are bringing heightened attention to the friction between herding and other economic activities.

We see this dynamic at play today in Mali and Burkina Faso. Fula communities across these neighboring countries may be found living as homogeneous groups in villages or settlements, in mixed communities in rural areas, or in multicultural, multiethnic urban environments such as in the cities of Ouagadougou or Bamako. Historically speaking, there is nothing in the relationships between Fulani and the ethnic groups with whom they live side-by-side that would suggest any predilection for violence—centuries have passed without incidents of what is misleadingly termed “ethnic conflict.”

However, like much of the Sahel, Burkina Faso and Mali are confronting poverty and climate change, the latter resulting in extreme weather and desertification. Increasingly intense competition for dwindling land and resources can all too easily lead to conflict. Cattle grazing on cultivated crops can have a catastrophic impact on farmers; conversely, grazing corridors or water sources blocked by cultivation may doom entire herds. Failed harvests or lost livestock assets can mean life or death for families, so it is unsurprising that people react strongly, sometimes violently, when they feel their livelihoods are threatened. As climate conditions and conflict make income increasingly unpredictable, people take drastic measures to protect what is theirs. Economic divisions take on increasingly ethnic dimensions as people band together in the face of what becomes perceived as a common threat. Communities take a step closer to communal violence.

Needless to say, then, these tensions are about more than loose words. But when development organizations fall prey to the pastoralist trope, we reinforce a narrative whereby Fulani are pigeonholed as pastoralists and implicated en masse in those underlying tensions. This sloppiness is inexcusable in areas at risk of communal conflict and mass killings, which is increasingly the case in Mali, Burkina Faso, and other countries across the Sahel, where Fulani—partly as a consequence of stereotyping language—are associated more and more with violence and, by extension, with extremists.

As development actors, we must be sure that the language we use does not reinforce conflict narratives or magnify suspicions between communities. We can also tackle the broader issues around how language can lead to, exacerbate, or perpetuate conflict, as DAI is doing in various countries—working with young people and others to spread messages of peace, monitor derogatory language, and set up communication groups to stop the spread of inflammatory rumors. Beyond that, we can support organizations such as Tabital Pulaaku, which is working internationally to raise awareness of the richness of Fulani culture, address the stigmatization of Fulani in the Sahel, and advocate for more sensitive integration of Fulani peoples into national dialogues.